The US Federal Reserve is locked in a high-stakes showdown with markets.

This week, chair Jay Powell won plaudits for acknowledging a rapidly brightening economic outlook and the chance of a push higher in inflation, while emphasising his commitment to keeping interest rates at rock-bottom levels for the foreseeable future.

But this relaxed attitude to inflation is biting in to the price of long-term US government bonds, sending ripples across global markets. Despite Powell’s hands-off approach to the rise in yields, in contrast with his peers in the eurozone, investors are continuing to question how long the Fed can allow this to run.

“It is not the level of yields that matters, but how it interacts with risky assets,” said Gene Tannuzzo, global head of fixed income at Columbia Threadneedle Investments. “If yields are moving up at a pace that is causing the stock market to fall and credit spreads to widen, then [Powell] will be a lot more concerned.”

In just the past week, the yield on the benchmark 10-year note jumped as high as 1.75 per cent, having traded around 1.6 per cent just days earlier. Since the start of the year, long-dated Treasuries, which mature in 10 years or more, have dropped almost 15 per cent on a total return basis, according to a Bloomberg Barclays index. If those losses are sustained, the first quarter of this year will mark the worst since at least the early 1970s.

The decline reflects a large upgrade among economists of inflation and growth forecasts, and a suspicion that the Fed will eventually be forced to bring forward its first rise in interest rates.

The European Central Bank has pushed back against the rise in yields on its turf, fearing a harmful rise in borrowing costs for companies and individuals at a delicate economic juncture. In contrast, the Fed chair has brushed off any unease, despite the ferocity of the move at times, in sharp contrast with the March 2020 episode when policymakers were in constant contact with banks and other market participants about the chaotic market moves.

The swiftness of the sell-off, which has begun to spill over into equity and credit markets, has rattled investors. In February, yields breached even some of the toppiest forecasts for the year, after a poorly received Treasury auction kicked off choppy trading.

Powell again dismissed the recent gyrations in the $21tn market for US government debt on Wednesday, reiterating that financial conditions across a variety of metrics remained “highly accommodative” and that the central bank would be concerned only about “disorderly” moves that threaten to undermine the economic recovery. To drive home the point, he suggested no intention to adjust the Fed’s $120bn monthly bond-buying programme.

“The market might push them to make a change in their behaviour but for now [Fed policymakers] have clearly indicated they do not want to directly participate in having an impact on the yield curve,” Rish Bhandari, a senior portfolio manager at hedge fund Capstone, said.

Mike Collins, senior portfolio manager at PGIM Fixed Income, warned that another sharp rise in Treasury yields could test their stance, however.

“Financial conditions do remain pretty loose, but if rates go up another [0.5 to 1 percentage point], that could really slow things down,” he said. The blowback in equity and credit markets could also be severe enough to prompt verbal intervention from the Fed, or even a shift towards the Fed buying more longer-term debt.

How the economic picture evolves as summer approaches could make the situation even thornier for the Fed.

Economists have already pencilled in a pick-up in consumer price increases this year as the economy reopens — a rise Fed officials say will be temporary. But the central bank’s endorsement of higher inflation, with its recent commitment to let inflation run hot to make up for past periods of undershooting its 2 per cent target, coupled with the enormity of the fiscal stimulus package recently signed into law have investors on edge.

“Markets have become incredibly concerned that the Fed will make a policy error in terms of higher inflation,” said Saira Malik, head of global equities at Nuveen. “The market can handle an increase in yields, but it needs to be orderly and driven by stronger growth and not going higher because the economy is overheating.”

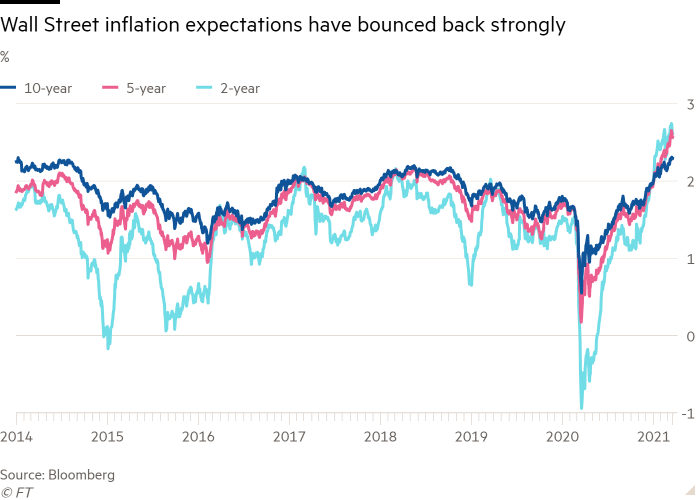

Brian Rose, chief economist at UBS Global Wealth Management, said he was watching longer-term inflation expectations closely for any sign that inflationary pressures could become destabilising. Five-year break-even rates, which are derived from US inflation-protected government securities, now hover around 2.6 per cent, just shy of the highest level since 2008. The 10-year rate is slightly lower at 2.3 per cent.

“If they are too successful and inflation expectations threaten to become de-anchored, then it becomes an issue and would make it a lot harder for the Fed to maintain very loose policy,” he said. On Wednesday, the so-called dot plot of policymakers’ interest rate projections implied that the central bank would keep interest rates close to zero until at least 2024, despite the sharp upgrade in its growth forecasts.

“There is nothing for now that tells us we are entering a new inflation regime that will . . . force the Fed to tighten,” said Diana Amoa, a fixed income portfolio manager at JPMorgan Asset Management. “That said, there is a lot more uncertainty around that.”

"term" - Google News

March 20, 2021 at 05:18PM

https://ift.tt/3r5VYXg

Wall Street tests Jay Powell’s mettle as long-term bonds tumble - Financial Times

"term" - Google News

https://ift.tt/35lXs52

https://ift.tt/2L1ho5r

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Wall Street tests Jay Powell’s mettle as long-term bonds tumble - Financial Times"

Post a Comment